I guess it won't surprise anyone that Port Alice didn't have a movie theatre, so I saw most of the movies that shaped us Gen Xers (more-or-less; technically I belong to the last gasp of the Baby Boom) on TV at a later date. Star Wars IV and 1982's Young Doctors in Love are exceptions, and, of the two, A New Hope was the better movie. Does Young Doctors in Love even have a life support/heart-lung machine scene? I guess it also won't surprise anyone that I am not going to rewatch it to find out! It's probably not nearly as hilarious as I remember, from the look of the Youtube extracts I watched looking for a heart-and-lunch machine scene. This one's got the surgical theatre-blinking-lights machines, so it will do, and I will preserve my nostalgia for a time just slightly past.

Because times change! Way back on 24 September we covered the President's actual heart attack of 1954 in the context of a presumptively rumoured one of 1953 (that is, rumours of a previous heart attack came up during the post-hospitalisation press conference. I am assuming without proof that this is people taking a conspiratorial view of the President's 1953 flu hospitalisation, which seems to have dropped down the memory hole as far as the Internet is concerned, but, Goddamn it, it happened!

|

| Magamp module, collection of the Avionics Museum, Rochester |

|

| "Brukhonenko's Autojektor" |

Fortunately, the machine was later developed into a production series at Francis Kellerman's (he can't be obscure; there's a walk named after him in Colchester!) New Electronic Products, Ltd, and an example built in 1958 was donated to London's proprietary museum. An actual physical specimen is hard to memory hole, and the Science Museum online exhibit has some scanty details. Specifically, it was designed by D. G. (Dennis) Melrose, better known for discovering the role of potassium citrate in stopping the heart. This leads me to the full biography at the Royal College of Surgeons site, with an entry that must of been written by that one son who lives in his Dad's shadow forever, because the entry says, unabashedly, that "Dennis Melrose played a crucial role in designing and developing the first heart-lung machine." It also gives me Francis Kellermans' name and Hungarian emigre origins, although not much else about that worthy.

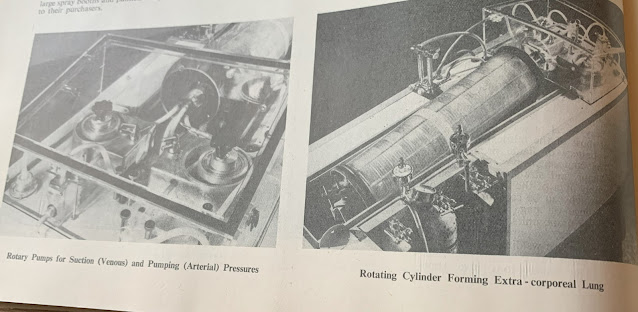

The Engineer article describes the control apparatus of the heart-lung machine, which ideally would be automatic, but probably is nowhere near close to that in 1953, in some detail. The basic point being that we need the machine to back off what it is doing if the patient gets too hot, blood pressure rises too high, and so on. The mag-amp is favoured for giving speed control of the pump, and controlling the valve on a reservoir of blood in case pressure begins to fall. That makes it effectively the master unit for the pump. I'm not clear on whether the heater is similarly controlled, but you would think so.

Anyway, it looks like the first successful cardiac operation in Britain was with the Melrose/Kellerman/NEP machine and not the prototype pictured in The Engineer, and it was in 1957, so several years after Kirklin's surgeries in the United States, so the inference is that the British team spent a few more years getting things right with their "heart and lung" machine before daring open-heart surgery with it. Hugh Henry Bentall,along with Bill Cleland, is credited with the first (unsuccessful) open heart surgery in the UK "in 1953" and later joined the Melrose/Kellerman team, and an obituary based, it seems on a colleagues Arthur Hollman's recollections, notes that Melrose's machine "was not, of course, the first such piece of equipment." Ironically, the Melrose team's climactic moment was an open heart operation in Moscow for an almost unheard-of audience of Soviet surgeons who "[S]aw Melrose's machine at a trade fair somewhere" and invited him to Moscow to demonstrate it, the team flying home in a Tu-104, "the Russians' copy of the UK's Comet." Maybe the Russians were catching up on old numbers of The Engineer?

|

| By Lars Söderström - http://www.airliners.net/ photo/Aeroflot/Tupolev-TU-104B/0168123/L/, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=4460512 |

As for the English Electric Magamp connection, a search brings me to this potted history of the company's Kidsgrove works, into which it moved in 1952 with various projects ongoing transferred in, including the "Luton Analogue Computing Engine," which sounds like someone was laying the foundations for a third Austen Powers movie; but the Magamp work there started with control units salvaged from V-2s. English Electric also borrowed its first transistor designs from RCA, so there is plenty here to give aid and comfort to the Audit of War crowd, just not the story of this forgotten bid for cardiopulmonary bypass primacy. It is, however likely that equivalent technologies to the Magamp existed in Britain already and the issue is more one of recognising that all these things are the same thing. Arthur Cable's online memoirs explore his work with "the Illgner System" at the Steel Company of Wales works starting in 1950, a technology which was not then seen as using a "Magamp" because the word did not exist for what was, after all, a "controller" and not an "amplifier." (The difference being a matter of the arrangement of the logic gates.)

That being said, I've no reason to doubt that the Melrose/Kellerman design used English Electric Magamps explicitly modelled on the ones recovered from V-2s. So that's what I've got. No neat conclusion all wrapped up in bows, just a series of historical anecdotes framed around this episode in history of technology; another forgotten chapter, and, perhaps, grist for some kind of argument that British embarrassment and reticence about the jingoistic excesses of the "New Elizabethan Age" might be flipped on its head and turned into evidence that the "New Elizabethan Age" was an abortion, and not a stillbirth.

No comments:

Post a Comment