|

| * |

Lutz Budraβ writes that interwar aeronautics couldn't really get it together until government-funded research into dirigible design gave them a mathematical basis for building heavier-than-aircraft.

So of course when Claude Dornier sat down to design a --transatlantic, I guess?-- passenger liner in 1924, it turned out to be bigger than a dirigible. The Wiki article says that the Do X weighed 56 metric tons, I assume all up, and was meant to carry 66 passengers on transatlantic flights. But then it also says, after admitting that it took nine months for the Do X to fly from Hamburg to New York, that it was the Great Depression that prevented Dornier from selling any more planes.

Technology enthusiasts are what they are. Facts, especially when they sound like pessimistic old people facts, have difficulty penetrating their invincible carapace of optimism. For every Do X in the past, there's a Mars Direct in the future.

C'mon! It'll be cool!

The issue here is that we're still talking about the Battle of the Atlantic as though it was won by magic aeroplanes, as though the main issue is that the planes right now seventy years ago today fighting the Battle of the Ruhr should be flying something called the "Gap," conceived as a point a certain distance between Newfoundland and Britain when it is in fact a function of weather almost entirely.

I've talked about the reality versus the fiction of "Very long range aviation" as a question of fuel octane ratings, avionics, mass production and tactics. I could talk about it as a debate conducted in the letters pages of the RUSI Journal in the mid-1950s between Stephen Roskill and some of the old bomber barons, who in my opinion schooled the official historian quite thoroughly, only to be lost in obscurity because they didn't get to write the official history.

One thing that I haven't written is a history of the bare-headed, addlepated ride into the future that was the interwar very large aircraft, a story that highlights just how extraordinary the four-engined heavy bombers that fought the Battle of the Atlantic were. There's a reason for that. If I started writing a facetious history of interwar aviation technology, I'd be here all day. This is, after all, the era that gave us a phantom German raider catapult-launching a diesel-powered flying boat bomber against New York from southern James Bay and a "flying family," complete with two children and a videographer, who tried to fly the North Atlantic via the polar route across Greenland in a Nordman flying boat, possibly with the discrete assistance of Charles Lindbergh, who did not realise until too late that people might be more aghast than amused by the irresponsibility of it all.

It's just that there's a version of this story (and I'm not going to ferret out someone who takes it seriously, so we're just going to have to write it off to old Professor Strawman**) in which the RAF was ready to send four engined aircraft to bomb Berlin on the morning of 11 November. And then they were called off, and it took 25 years for the air force to climb that hill again.

Well, to be sure, there is this:

|

| From Wikipedia |

That's 8 year-old Igor Sikorsky's Ilya Murometz, the world's first four-engined strategic bomber. However, as the Wiki article also notes, this "strategic" bomber had an all-up weight of 12,000lbs. The Vickers Wellesley managed 11,000. It seems a little surreal, an impression reinforced by a look at one of the British "four engined bombers" of 1918, the Handley Page V/1500:

|

| Wiki |

The staggered, close-to-the-fuselage arrangement of the engines on the Handley Page job reflects the fact that Freddie, who, let us not forget, was an actual engineer out of the electrical industry, where you actually had to do maths, didn't feel that he could stress the outer bays properly to take an engine. The difference is probably to be found in the variation in all up weight: 30,000lbs versus 12,000.

At the same time, you probably want to look at the first, few chapters of Hyde. The big bombers were ready to take off and raid Germany in 1918, but when an armistice supervened, they were flown, equally frantically, east. Unprepared for the end of the war, the British government was caught by surprise by the expiry of its emergency powers, which left it with no airfields and no hangars for these monsters. After four years of research and development, the only way that the RAF could save these planes was to get them --somehow-- to Port Ismaili in the fabulous east, where the weather was always sunny and the runways were long. Which is how, if you're interested, the V/1500 came to fly its one operational sortie against the palace of the King of the Afghans. "The ladies of the royal harem rushed onto the streets in terror, causing great scandal," Wikipedia quotes Chaz Bowyer quoting I know not who.

If only the Afghans didn't harbour such irrational and ignorant prejudices against foreigners, this might have been the end of all Afghan wars, one imagines.

Again, the story is, as framed, a little surreal. To get it back on track, nothing is more bracing a corrective than the article on "Giant Aircraft" in a 1920 number of the little quarterly published by the Aeronautical Society that would eventually become Jour. Roy. Ae. Soc. that has apparently dropped out of my bibliography. It's mostly a descriptive account of the big planes under development in the various belligerent nations in 1918, but even in its infant state, the Journal made efforts at scientific merit, and it included the results of stress tests on structures by the rough-and-ready method of hanging sandbags off them and measuring deflections.

The results are eye-opening. None of these aircraft had a stress factor greater than 5x, and in some critical parts it fell as low as 2.5. Remember when you were a kid, and you learned by bitter experience that your build-your-own-Lego space aeroplanes couldn't have really big wings, because the weight tended to cause them to fall off the fuselage? Exactly.

I got in a bit of a dustup over at Brett Holman's blog once over the fact that people were designing these planes without (yet) having working wheel brakes. My point was that it was scarcely clear that they could climb fast enough to clear obstructions at the end of the runway, and without brakes, they couldn't land, either. That's a little crazy. It is also less than clear that the brakes would have been critical in planes that couldn't yet be equipped with tail wheels on account of no-one being able to design workable tail wheels for structures this heavy yet, so that they still used skids. But, then, how much would that matter when George Dowty's pioneering self-suspended wheel was still years away? A heavy landing onto a fragile undercarriage with no shock absorbers doesn't sound very promising, either.

Oh, and as for that toss-off about not necessarily being able to clear an obstruction at the end of the runway? In the mid-20s, they were still arguing about whether what they called "clear-air turbulence" existed. As part of that debate, C. G. Grey tried to get the British Air Ministry to waive its already quite low minimum climb rates for pioneering aircraft on the grounds that they probably wouldn't have to try to take off in a sudden downdraft. The Do X took 50 seconds to break the water and takeoff in its famous proving flight, and then "slowly" climbed to a ceiling of 200 meters. You can probably guess what would have happened to it had some "clear air turbulence" come along.

Just to show that Claude Dornier wasn't some lone visionary, let's join together and point fingers at another freak and laugh:

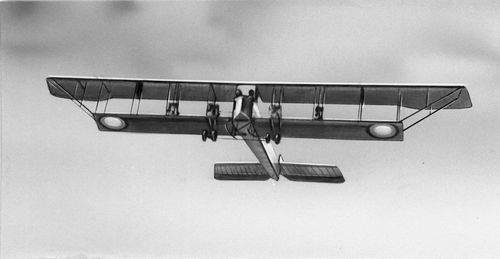

|

| Wiki |

This is a real plane that happened. In its final version, flying in the mid-1930s, the G-38 carried 6 passengers in each of the two wing compartments and an additional 22 in a two deck fuselage passenger section. At one point, the Wiki article says, there were two G-38s, but I distinctly recall Flight pointing out that the Lufthansa pilot attached to the G-38 was a six foot 8 inch (204cm, if I'm converting right) Viking, the only man in the fleet with the strength and leverage to move the plane's controls.

This had something to do with the Junkers "double wing" design concept, a distant predecessor of modern variable geometry via early landing flaps, and also with the thick wing, which was intended, aside from giving additional strength, to allow the flight engineer access so that he could go out and adjust the engine carburettor needle valves by hand. (Which, by the way, was the intended use of the little engineering compartment that is inside the weird top parasol of the Cataline PBY. The Zero, on the other hand, more practically just provided an adjustment switch on the pilot dashboard, one of the secrets of its long range performance, in this last era before the invention of self-adjusting carburettors.)

Though it probably had more to do with the design being absolutely crazy. That being said, British Airways was as convinced as anyone was of the virtues of four engined configurations. That is why old Heracles stuck around so long:

|

| Wiki |

Long after a more "modern" four engine plane elicited so much attention in America that it actually earned its own spread in Aviation and might have inspired Boeing to enter a four-engined aircraft into an Army Air Corps bomber competition as a backdoor pilot for a four-engined airliner.

|

| Wiki |

It turns out, however, that if you're designing an airliner that is going to have to smash through giant ant hills on its landing runs on airfields built down the mountainous spine of East Africa, you probably shouldn't put spats on the wheels. And you should also maybe refamiliarise yourself with the concept of economy of effort.

The next major effort along these lines was a showcase for the Armstrong-Siddeley Civil Tiger aeroengine. You're probably thinking right now that you've never heard of an Armstrong-Siddeley Tiger, and perhaps that doesn't bode well for this modern looking airplane:

|

| Armstrong Siddeley Ensign |

And it's true. At least the camouflage paint wasn't wasted. Any plane that spends as much time as this 14 aircraft production run did on the ground in wartime needs to blend in with the grass. You could probably make up some Barnettish story about this plane, which was only saved by installing Wright engines, not much of an endorsement considering the Wright engine shop's reputation.

But before Americans pat themselves on the back, there's just this:

|

| DC-4E |

That's the would-be DC-3 successor that so embarrassed Douglas that its name was shifted to another plane. Which also failed, only to be saved by the armed forces, which were willing to re-engineer it into the legendary C-54, which became the basis for a DC-4 that actually lived up to the legendary name when it debuted in 1946.

Notice the triple empennage at the back, which you will see in practically every big aircraft of the 1938/39 era. Not every pilot is a Viking. The small rudders could actually be shifted by the strength of a normal man. So it's a pity that they didn't actually work.

With all of this experience behind them,*** it is no wonder that the international aviation community was ready to jump on the RAF's specification for a bomber for "worldwide operations" that was armed with power turrets, could carry 2000lb armour-piercing bombs, could use catapult-assisted takeoff, carry two torpedoes, be capable of dive bombing, cruise at 275mph, and, in a pitch, carry 22 passengers. (The idea being that the planes would fly in their ground crews, not that they would serve as bomber transports.)

Ta-da!

|

| Avro Manchester |

Give Air Ministry Specification P.13/36 credit. It was a serious attempt to address the global strategic liabilities of the British Empire. One of the little surprises packed into Chris Shores et al.'s Bloody Shambles is that a day-by-day, sortie-by-sortie reconstruction of the air war in Malaya in 1942 showed that this global vision worked. You can follow the inward trickle of RAF Lockheed Hudsons through the volumes on the defence of Malta to their arrival in Malaya, where they and their crews did some small amount of good, notwithstanding the fact that the planes that the Air Staff was sending down the long middle passage from Britain to Malay weren't very good. Imagine now that instead of packets of Hudsons, it was a mighty strike wing of Avro Manchesters. Wouldn't that have changed the fate of the world?

Well, maybe. If the Manchester had been any good. Which it wasn't. On the contrary, pretty much everything that could be wrong with it, was. The failure of the plane normally gets laid off on the engine, which was a failure waiting to happen, although legend has it that all of the bugs were worked out just before it was cancelled. (Which I kind of doubt. This is an even more complicated layout than the Sabre. There were a lot of interwar "Xs" and broad "Ws," none of which made it into largescale service.) That being said, the plane's look spells incipient disaster. The Lancaster admittedly made the double empennage work, but that's far from saying that it was a good idea, and the weights (31,000 empty, 50,000 auw) only need to be compared with the Lancaster I (36,500; 68,000) to tell the story of the rate of improvement in Avro's weight control practice between the two designs.

I come back to Lutz Budraβ's point. It is easy to slap something together that will fly, and, to an extent, simple experience will tend to make them better. But the world of aviation is moving, very rapidly, from one of amateurs playing with shapes that they can make with skillet saws to that scary mathematical-type stuff. The planes that I've featured here look, quite frankly, like offences to common sense, but "look" isn't proof. The issue is that they exist at the cusp of the moment when it was possible for the industry to talk about things like proof.

For those tempted to immersion in the transient crises of modern politics, it might even be salutary to remember that there h ave been other groups of people to reject membership in the "reality based community."

Now: About Mars Direct.

*It flew once. Photo from Aeronautical World Experimental.

**Professor Strawman got tenure in 1964, the year that the Baby Boom showed up at the gates of Ivy University. His textbook is widely recommended, and every year he teaches an extra-credit summer course on German history on a tour boat that descends the Rhine from Lake Constance to the Dutch border.

***And bear in mind that I'm only hitting the highlights here. Oy. And to qualify this post for my continuing Patent Troll series, here's Vincent Burnelli. Wikipedia doesn't really grok the crazy, but fortunately Google turns up "The Vincent Burnelli Conspiracy." Enjoy.

I didn't know the Soviets invented the in-flight movie!

ReplyDelete"It was intended for Stalinist propaganda purposes and was equipped with a powerful radio set called "Voice from the sky" ("Голос с неба", Golos s neba), printing machinery, library, radiostations, photographic laboratory, and a film projector with sound for showing movies in flight."

Semi-random fact: something like two billion dollars (potential factoid alert!) was invested in aviation in the United States in 1929. So if you're going to think about aviation in the early 30s, maybe the dotcom bubble is the right paradigm. The Soviets could hardly offer stock options in Antonov, but there was definitely a sense that you built the technology first, and profits would somehow follow.

ReplyDelete