|

| Original Industrial Aviation image drawn by Reynold Brown and hosted by Randy Wilson. |

The chief technical designer at Republic Aviation, Nicholas Mastrangelo (and there's a name that would tell a story if Google would only yield to it) described the Republic P-47 as "[the] culmination of the knowledge gained by years of high speed airplane design." Someone else, who talks like a mid-century ad man (or comic book writer, the difference is moot) put it less modestly:

Introduced as a high altitude, offensive fighter, the P-47 with eight .50 cal machine guns, was later equipped with supports for rocket tubes and a cluster of demolition bombs. It can also function as a ground strafer, tank buster, tunnel buster, hedge hopper, and dive bomber. With a bomb load of 2000 lb. capacity, its weight is more than 7 tons. Powered by a 2000 hp, 18-cylinder Pratt & Whitney engine, its speed is in excess of 425 mph; range more than 1000 miles; ceiling about 40,000 ft. Wing span is 41 ft.; lenght 36 ft., 1 ¾". Propeller may be either Curtiss-Wright electric or Hamilton Standard, hydraulically controlled, constant-speed, four-blade assemblies. (Hamilton Standard type shown here).

Just so you know that the USAAF had a plane to fill the vital "hedge hopper" and "tunnel buster" roles.

If you're struck by the idea of hedge-hopping in an aeroplane with a wing loading of 58.3 lb/sq. foot (compare 49.4 for a fully tricked out FW190 or 39.9 for a De Havilland Mosquito),* I assume it's because you're some girly-man European. Ask yourself: am I a cheese-eating surrender monkey, or do I like cal .50s? I think the answer will fall out of the exercise quite neatly.

And now I am done being unfair to Mastrangelo and Republic Aviation. Alexander Seversky at the height of the Depression, won a fighter contract with the P-35, went on to get the P-43 flying, and was well into seeing it developed into the P-47 Thunderbolt, a plane that was only freakishly gargantuan because nothing smaller could support the engine and supercharging configuration into which Wright Field had locked America's domestically-designed pursuit force. At which point he was forced out of his own company by "financier Paul Moore," to quote Wikipedia.

It could have been worse. The P-47's rival was an "air superiority" type that had to form up in defensive circles when intercepted by enemy pursuit:

And when the iron requirements of thrust-to-weight ratio were relaxed by the addition of "night fighter" to the specification, the West Coast decided that the futuristic looks of the Lockheed Lightning were so cool that they justified a fighter that was bigger than a medium bomber. What must have been especially aggravating for Seversky is the planes that the War Department ordered in preference to the P-43. The Curtiss P-40 at least extended an existing line of pursuit fighters, capitalising on existing expertise, but only at the expense of accepting a GM engine with an obsolescent single-speed supercharger. The other winner was by a first-time entrant that combined the same engine choice with a freakish, doomed configuration.***

So I've said "freakish" several times. That brings me to the actual topic of this post, to wrap around eventually to War Department procurement policy.

Leaving the Flechair aside, the "freaks of 1939" could hardly be better summarised than by this: (yes, I'm really giving Wikipedia a workout here.)

To the extent that the Fokker D-XXIII has an excuse, it's that the house's last spring style went over so well. I mean, how do you top this?

Sometimes, the freaks are less obvious. A regular guest on these pages:

Ultimately, the Whirlwind failed because you don't impose twenty-four spark plug changes on the ground crews when twelve changes will do the same job. That being said, the design screams "too clever by half." Surface radiators, internal exhaust, magnesium monocoque fuselage? Ted Petter turned 30 while developing the Whirlwind. An amateur psychologist (that's me!) would suggest that this is what happens when a man in his 20s is trying to find his way out from under his father's shadow. I won't presume to guess about his grandfather's, but I will venture to suggest that the man who got the Whirlwind out of his system and went on to design the Canberra had a chance to laugh in later life about his father's decision to sell out of the company's mechanical calculator business in 1935. No future in those contraptions!

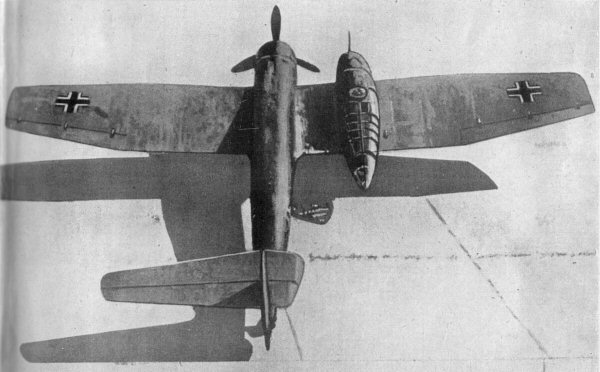

Coming back to the D-XXIII for a moment, the design will probably remind the reader of the single-most-wanked over plane of World War II

even if it differs in not having the engines in-line, muddying the advantages of reduced profile drag but eliminating the extension shaft. My hyperbolic and obscene choice of language suggests a low opinion of the Do-335's fanboys, which I think is justified by the rather obvious point that the Dornier firm had been dicking around with the front-to-back configuration for over a decade by this point without much to show for it for the simple reason that it is an answer in search of a problem. There is no technical issue that it solves that is not better solved by a more conventional twin-engined configuration, and that Dornier had lost its mind is even better suggested by the Do-635, a proposed twinning that would have produced a single-seat reconnaissance aircraft with the all-up weight of a late-model Lancaster. Words would fail.

So, yeah. This is what a post-Seversky Republic thinks is a sensible design. 17,000hp, 102,000lbs all up. To take pictures for B-29 strikes. Now, sure, the further you push your photoreconnaissance requirements, the bigger the ship is going to be. But maybe a stripped B-29 could do the same job? Just throwing it out there. (Though the real reason Republic persisted was that it was dreaming of airliner contracts.) And there was even a slightly more reasonable alternative. Which, coming from the house that produced the Spruce Goose, is saying something.

We'll leave out poisonous rumours about Roosevelt family financial stakes in the future of either project, brought to a none-too-untimely close by the relevant congressional committee's decision to adjourn rather than take the next step of indicting Hap Arnold. It's not that I think that Kermit Roosevelt was really at the wheel when the prototype XF-11 crashed. I'm just being mischievous.

Is there a point here? In a lapidary judgement delivered by John Fozard, allegedly directly from the lips of Sydney Camm, the real history of fighter design and development from the Camel to the Harrier is eyeglazingly boring. You take what worked last time, work in about 20% novelty, and get a programme that costs a predictable number of labour hours/production numbers on a strict linear curve leading from the aforesaid Camel to the Harrier, and, one assumes, to the F-35. Or something like that. I'm going on memory here.**** Obviously, some planes succeed and others fail, and the airframe designer is in the hands of the engine developer, and, more importantly, Kingston-upon-Thames is likely to be Whiggishly self-satisfied looking back on an unbroken line of development in the way that, say, the Bayerische Fleugzeugwerke would not be, and I assume that there's a reason why Fozard's Wikipedia biographer mentions that he died of liver failure at 68. All that said, there's something to be said for going from

to

to

to

I am not going to fight in the last ditch to defend a process that produced a plane that was obsolescent when it fought its major battle, much less an outright failure like the Typhoon. My point comes back to the one I made at the start. A design house that is given a chance to work within an incremental tradition is unlikely to produce one of the "freaks" that have so far graced these pages.

My point, rather, is that the freaks are symptomatic of something different. Novelty is being substituted for incremental improvement because the design houses have no idea what they should be building, and the relevant ministries are incapable of taking them by the hand. World War II aviation technology development stands out as a singularly clear place to demonstrate that actual innovation is very, very boring compared with what happens when people have no idea what they're doing. I'd say something more dramatic were it not the case that Nathan Rosenberg said it a generation ago and no-one listened then.

But if it is not clear what got me riled up enough to post this morning yet, let me plead once again for the role of experience and incremental improvement in the history of technological innovation, and against those who propose that the future belongs to wunderkind with STEM degrees and high school graduates making coffee because, in the high tech world of the future, there will be no place for those so stupid that they had to toil on the assembly lines of the past, where no innovation ever took place.

Nick Mastrangelo again:

Although the four-bladed propeller was an admirable solution to the power gearing of the engine, there remained the problem of landing gear height. If minimum ground clearance for the 12 ft diameter propeller had been maintained by the conventional landing gear, its suspension would have been too far outboard . . . [so that] the same firing power were to be maintained. . . .Republic designed . . .. [the first telescopic landing gear] . . . the landing gear is 9" shorter when retracted.

(edit)

Okay, now look at this:

It's not immediately obvious from the "warbirds" style picture, but this is the plane that Nick Mastrangelo is taking a dig at. Another Double Wasp-fighter, imposing the same kind of ground-clearance issues, albeit rather the worse for choosing a three-blade airscrew that needed 13ft 4' vice 12ft to achieve the same blade solidity. Vought famously chose a bent-wing configuration to give enough ground clearance. (Grumman solved the problem a third way, with a mid-wing configuration. Notice first that this required putting the wing spar in the middle of the fuselage. Notice second that they had a great deal of experience (1, 2) in doing just this.)

When the prototype Corsair flew for the first time in October of 1939, it clocked in at 405mph, although by this time claims of 400mph were old news and boring, so Aviation made it a "500mph" fighter. (It also made the prototype Liberator a "400mph" bomber.) The Corsair turned out to be a pretty good fighter for Navy work, once its problems, many of them self-imposed by the inverted gull wing configuration, were solved. Indeed, at one point it was barred from carrier operations and relegated to general purpose fighter-bomber work, perhaps the most extreme example of the relegation from pursuit to indifferent bomber suffered by so many wartime would-be chasseurs. (A video that could use some editing.) Fortunately, Pratt & Whitney was able to put a good-enough-for-Navy-work two-stage supercharger on the plane, and since safe landings were often a secondary consideration even on good fighters, the Vought machine survived in service to win a sterling reputation for the company's first fighter.

Okay, now back to Seversky/Republic.

See these guys? They're working on Republic's third fighter design in five years. Not, oh, say, serving coffee or teaching yoga.

That guy on the left, with the questionable fashion sense and the build of a guy who hasn't done a lot of heavy work in many years, but without the glasses that would mark him out as a poindexter? He's what you call a "skilled tradesman." The rolled-up flannel shirt suggests to me that he's down from the moulding loft, but, shh, don't tell Corelli Barnett that, because I expect he'd be crushed to learn that people were laying out planes with sticks and string in attics in America, too. (Talk about the lost quotidian.)

The guys in the foreground? They're assembling a fighter plane, which in this case seems to consist of trying to fit a panel onto a frame while the tradesman thinks deep thoughts about whether it should come up a bit or down an inch or so. I

Now, in the perfect world of the "inventor," they're on an "assembly line" making real and embodied the thing drawn, which is this.

The guys in the foreground? They're assembling a fighter plane, which in this case seems to consist of trying to fit a panel onto a frame while the tradesman thinks deep thoughts about whether it should come up a bit or down an inch or so. I

Now, in the perfect world of the "inventor," they're on an "assembly line" making real and embodied the thing drawn, which is this.

Doesn't look much like an assembly line, does it? That's because an assembly line isn't an assembly line, or some such Po-Mo slogan. In the world of our bourgeois imaginations, an assembly line is the kind of place where Charlie's dad worked, tightening the caps on toothpaste tubes all day.

In the actual world, both the guy in the checked shirt and the guy involved in a two-sided relationship with Mr. Mastrangelo, who most certainly did not draw every fitting, every rivet, above, because who has time for that? Because I have already made fun of it, it might not be clear how much I admire the ability of the team that created a 17,000lb single-engined fighter that could exist in the same sky as planes half its all up weight. The structural ingenuity of a thing that could be hauled around by the engine that the War Department locked Republic into are lost to us because the only way to appreciate what they achieved is to have hands that are capable of making it. When there are no hands that can make, we get flailing instead: the freaks of 1939.

Therefore, of technology, of which we cannot make, thereof we must not speak. Or, to put it another way, with all due respect, the whole "deskilling of the modern economy" and "the future belongs to robots"thing needs to chill. The only likely consequence of talking like that is to justify paying the people who embody technology less.

*You could probably produce comparisons more favourable to the P-47 by taking different estimates of all up weight, but I think the point will stand.

**It's hard to judge these things at a distance. Maybe Seversky was a bad CEO. Perhaps he was already the telling-truth-to-power maverick that comes out in Victory Through Air Power, or perhaps the bitter willingness to suggest that the the American air effort was ill-managed reflects recent experiences. That bitterness was warranted is strongly suggested by a little more Wikiplagiarism. Enjoy your own 'threw up a little in my mouth moment":

"[Paul Moore was the] son of William Henry "Judge" Moore and the father of the Rt. Rev. Paul Moore. [Paul Moore] was a member of the Yale Class of 1908. He earned a law degree, 1911, from New York University.

After graduating from Yale, Moore started his career in the law office of the Rock Island Railroad in Chicago. He enrolled at Northwestern University School of Law while there but returned to New York and completed law studies at NYU. During this period he married and was a director of the Lehigh Valley Coal Sales Company.[1] During World War I he was a major with the Army Ordnance Corps.

Moore married Fanny Mann Hanna, a daughter of Leonard C. Hanna and niece to Mark Hanna, on October 30, 1909, in Cleveland, OH. Mrs. Moore was a member of the Citizens Committee for Planned Parenthood of the American Birth Control League.[2] She was also the first female director of the Episcopal Church Foundation.[3] Paul Moore, Jr. would go on to be a leader in the church as the 13th Episcopal Bishop of the New York Diocese. He was a noted liberal advocate during and after the Civil Rights era in the United States of America.

Moore consolidated the gains made by his father, "Judge" Moore, during the corporate merger or "Great Merger Movement" at the turn of the 20th century.[4] He reorganized Seversky Aircraft to Republic Aviation in 1939, and sat on the boards of several enterprises put together by his father and uncle, James Hobart Moore, among them United States Steel, National Biscuit Company, Bankers Trust, the American Can Company, and the Delaware, Lackawanna & Western Railroad.

***Just to expand here: the Red Air Forces loved the P-39 because its nosewheel configuration eased training burdens, and because it was as good a low altitude air-superiority fighter as most domestic products. Contrary to the apologists, however, the P-39's weaknesses at high altitude were organic to the design as well as flowing from the engine. The reason that no-one else put the engine at the centre of mass was that then you have to put a heavy transmission shaft in. Good aircraft designs don't put extra weight in, and while nosewheels reduce ground accidents, they are also heavier than tailwheels and impose higher takeoff and landing speeds.

****Fozard,

John W. “Jubilees in Design and Development.” In Sydney

Camm and the Hurricane. Shrewsbury, U.K.: Airlife, 199. Ed. .John W. Fozard

.jpg/785px-Sea_Fury_FB_11_2_(5922456104).jpg)

.jpg/800px-Vought_F4U_Corsair_(USMC).jpg)

I may well regret this, but in what sense is the Typhoon an outright failure?

ReplyDeleteThere's also, if I'm going to risk all this regret, the XF5F, an obvious freak that won its flyoff.

Off-topic giant railway gun watch: http://www.theguardian.com/world/2013/sep/02/first-world-war-gun-railway

ReplyDeleteI'm calling the Typhoon an outright failure because it was built as a high-altitude interceptor and turned into a single-seat bomber. Which is, I reiterate, a good way to use un-needed fighters, but a bad way to invest resources in dropping bombs on people.

ReplyDeleteAnd, yes, the XF5F was good. All of the twin-engine fighters were good. Until they actually had to fight and be maintained in the field. This is kind of like the revelation that forty ton tanks beat thirty ton tanks, which beat twenty ton tanks. Or that Canadian football is more fun than American. Relax the restrictive dimensions, and you get more room to play.

If the Typhoon is an outright failure, how might one expect to see an aircraft like the P-75 Eagle described? Purely as a point of rhetorical calibration?

DeleteI'm not sure "close air support" and "dropping bombs on people" are the same category; fixed targets versus area targets (rail yards, staging areas for troops) vs targets of opportunity are all different problems. It's not clear anybody's ever solved the targets of opportunity problem in the general case for air support.

Fighter-configuration Mosquitoes do seem to have been good; the various Beaufighter variants, similarly. And the restrictive dimensions aren't a feature, surely?

You can't, if you're the USN, beat the Zero at being a Zero; it gets it range and manoeuvrability from a policy of expecting pilots both excellent and expendable, so you can give up defensive features to save structural weight and still have a successful aircraft.

If you eventually have to fly monster radials to beat the Zero the other way, on sheer speed and climb and fire power, there's no inherent reason not to have started with your eighteen cylinders distributed over two engines, is there?

Well, the case can be made that the P-75 was the Fishers' successful effort to avoid being saddled with a P-40 contract. Sure, it cost the War Department a great deal of money, but not nearly as much money as making more P-40s, and giving another GM plant a chance to dip into the pool of new industrial techniques is a long run good.

ReplyDeleteThe Typhoon, on the other hand, counts clearly as "failing forward." Kingston just plain got the future wrong, and the result was wasted money. As a CAS type, the Typhoon was barely an improvement on the Hurricane.

I say this because I read the role of CAS as essentially a means to impose friction on enemy manoeuvre. I suppose that CAS types have killed more enemies than friends in their long existence, you should not be using planes to do artillery work outside of a countrywide counterinsurgency campaign where the fighting is always out of range of the guns and the AAA threat is negligible. IMHO.

As for beating the Zero, I guess the argument can be made that a twin could have been made to work from a carrier. But no-one did it. And it is going to have to be a pretty big engine before the maintenance burden is less for two than for one. Spark plug changes make a good reference, but it is carburetors that make old-timey fitters blanche. Unlike electrics, which they can delegate. (And then whine about unreliable Lucas crap when the smoke shop can't work a miracle.)

As a CAS type, the Typhoon was barely an improvement on the Hurricane.

DeleteHurricane II was withdrawn in the fighter bomber role because it was getting massacred by FW190. Also, I'd consider "twice the bomb load" to be an improvement.

More bombs is awesome when you're using a fighter as a bomber. I'm just saying that that's what you do when you have too many fighters, and that it is not, in itself, a good role for fighters. That was an unavoidable fact of life in WWII. Major aircraft procurement programmes had a momentum that kept the types in production well after their sell-by date.

DeleteIn the CAS role, I am less convinced that more bombs is an improvement. The role of fire on the battlefield is suppression. More bombs only mean more suppression when they are delivered in a way that maximises effect in area and time. This does not describe a fighter bomber strike, regardless of bomb load.

On the other hand, a given CAS type gives more suppression effect when it dwells over the battlefield for a longer time. This is an effect of logistical and maintenance burden, not weapons lift.

Again, fighters are used in this role because they are surplus to the air superiority mission. The Typhoon never had a period in which it was part of the Allied air superiority solution. It might have had one in late 1941, but teething problems prevented it. (Not to carp: teething problems were also inhibiting the FW190. It's just of the essence of a Fokker panic that no one cares about such things. They care that there is a FW on their tail, and they can't get it off.)

Just to be clear, it is this context that makes the Typhoon a failure. It was a failure in spite of being very much of a piece with its contemporary, the FW190, right down to suffering from a virtually identical aerodynamic problem, and in spite of the FW190 being a threat to Allied air superiority. The Typhoon failed to fill that role because the Spitfire IX came along, not because of any inherent problems with the airframe, although one can certainly point one's finger at the engine --as, again, could Focke-Wulf.

This is a case of "failing forward," and I would not call the Typhoon a failure had it not been supplanted by the Tempest. This is, of course,a double standard. I do not call the P-38 a failure. I would if it had been replaced by a P-76 that took the P-38 concept and developed it into a first-class air superiority type. I am holding Hawker to a higher standard than Lockheed, and I am doing so to highlight the role of ministry guidance and institutional experience in technological development, over and against the myth of the innovating inventor.

The blog shows how technology has simplified the various impossible things in human life.Thanks for sharing the details.

ReplyDeleteRegards

Henry Jordan

Hydraulic Cylinder Seals