I'm on vacation in the third week of August, because that's what vacation is for. The schedule of my life therefore calls for the second part of postblogging May this week, followed by some harvesting of low-hanging fruit via the Technological Appendix series over the rest of the month, any book-writing being additional to a long-anticipated bike tour of the Kettle Valley railway right of way, now the Trans-Canada Designated Trans-Canada Bike Holiday For That-Kind-Of-Middle-Class-Person Route. I brunch, therefore I am. Own my authentic self, I say.

Unfortunately, all of this rational planning reckoned without my employer's grand plan to deal with the fallout of its mass buyout of "high cost" labour. After twenty-one years of complete failure of "low cost" labour to materialise, it might be a bit much to expect trends to change during the worst labour shortage yet, but . . . Well, let's let Wile E. demonstrate:

Other jokes about my employer's labour situation involve the "everything's fine" dog, cars driving off cliffs, General Custer and the Titanic. The upshot is that, because our dairy manager decided to betray the company by having a baby this week, I'll be doing his job tonight and making the big overtime money instead of, I don't know, writing.

Other jokes about my employer's labour situation involve the "everything's fine" dog, cars driving off cliffs, General Custer and the Titanic. The upshot is that, because our dairy manager decided to betray the company by having a baby this week, I'll be doing his job tonight and making the big overtime money instead of, I don't know, writing.

Or sleeping. Sleeping's good, too. So here's some low-hanging fruit., beginning with HMS Amethyst, courtesy of the Imperial War Museum.

Since this post is about Wassily Leontif's Project SCOOP and IBM's SSEC, that is, two obscure bits of the early history of computing that could benefit from a bit of light, talking about the Yangzi Incident is a bit of a stretch. Not, however, an impossible one, because there is some early computing history to the Black Swan-class, too, and also something to be said about communist revolutions and Fortune deciding to publish Louis Ridenour in May of 1949.

|

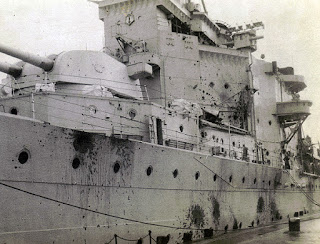

| The most damage a County class ever took in action. |

Brind does not appear to have been an early Cold Warrior. His appointments track Bruce Fraser's quite neatly, and he did not arrive on station until 1949, which means that he wasn't significantly involved in the early post-war attempt to revive the Yangzi gunboat squadron, over the Foreign Office's horrified objections. He did, however, become a latter-day convert at least by the aftermath of the Incident, when he got entangled in Nationalist attempts to blockade Communist-held Shanghai and other coastal ports. This doesn't seem to have affected his career any, or that of his second, who was actually in command at the time.

.

Brind's enthusiasm for a bit of a show on the river led to the creation of a "guard ship," whose task was to hang around the British embassy in Nanjing and give expatriates some reassurance that they would be evacuated in good order if and when the regime collapsed. From the British point of view, oblivious as always to the insult to Chinese patriotism implied by the presence of foreign warships on the river to begin with, this also shored up the Goumindang regime, since it ensured that people wouldn't panic and try to bail out before the rush.

The Australian government wasn't necessarily on board with this, and the guard ship, as the fourth week of April opened, was HMS Consort, due to be relieved by HMAS Shoalhaven, a Bay class frigate, which was basically a war-economy version of the White Swan by way of the River and Loch class ASW frigates. Consort was running short of supplies, and a ceasefire was in effect, and so, on 19 April, Shoalhaven was ordered up the river to relieve the Co-class destroyer, "as news reached Shanghai that the Communists were expected to cross two days later."

|

| Li Yaofu, before 1317 |

The Yangzi river typically experiences three discrete high water marks in a year: during the spring rains, the summer freshet, and with the return of rainy weather in the fall. The spring floods are typically the lowest, with rainfall beginning in May and peaking in June. This is why it is not uncommon for northern dynasties to schedule the final eradication of southern regimes for the spring, with a good, old-fashioned assault crossing of the Yangzi. I noodled around the Internet for some graphics and details, but the attackers tend to be the bad guys in modern Chinese historiography, which makes pulling out the details a few minutes work, and who has time for that? Besides, "Bodhidharma Crossing the Yangzi on a Reed" is far more evocative.

The Yangzi river typically experiences three discrete high water marks in a year: during the spring rains, the summer freshet, and with the return of rainy weather in the fall. The spring floods are typically the lowest, with rainfall beginning in May and peaking in June. This is why it is not uncommon for northern dynasties to schedule the final eradication of southern regimes for the spring, with a good, old-fashioned assault crossing of the Yangzi. I noodled around the Internet for some graphics and details, but the attackers tend to be the bad guys in modern Chinese historiography, which makes pulling out the details a few minutes work, and who has time for that? Besides, "Bodhidharma Crossing the Yangzi on a Reed" is far more evocative.

What I'm saying here is that Brind, his second, and the ambassador sure as fuck ought to have known that whatever ship was sent up the Yangzi to relieve Consort was going to be sticking its nose into the middle of a major military operation. The commander of Shoalhaven, who had orders from Canberra not to involve himself in any imperialist fiascos, perhaps did, and decline the invitation to proceed, at which point the Black Swan-class frigate, Amethyst, was substituted.

Some interesting facts about the Amethyst are in order here, saving the most interesting for later. Designed in the late pre-war period as a combination anti-aircraft/anti-submarine escort, the Black Swans boasted no less than 6 4" high angle guns, a very impressive gunnery suite for a ship of 1350t standard displacement, rather smaller than a destroyer. The somewhat similar Hunt-class earned a good reputation in shore bombardment operations at Dieppe and during the D-Day operations thanks to their ability to bring smothering fire in close to shore with their shallow drafts and heavy broadside of 35lb shells that were too light for naval work, but which packed more than enough HE for any land target short of a bunker.

I'm not saying that Amethyst was substituted for Shoalhaven with an eye to steaming right through a Chinese fire drill, as they said back in the day, dispensing a few 4" shells for the improvement of the masses if necessary, but I think that's the way the smart money bets. Especially considering that Amethyst anchored overnight on the 19th precisely so as to make its way through the crossing area after the morning mist had cleared. The appearance of a Western warship in the midst of crossing preparations had what, in retrospect, was always the likely result. Even festooned with British ensigns, Communist battery gunners were unwilling, or unable, to recognise a neutral vessel, and brought it under inaccurate fire, which rapidly improved in accuracy when Amethyst entred the narrower stretch between the northern bank and Leigong Dao, identified as "Rose Island" in the Admiralty sketch map below.

|

| Sketch source: https://www.naval-history.net/WXLG-Amethyst1949.htm. From a Parliamentary report. |

Quickly hit four times by a tight group of fire to the bridge, Amethyst lost its skipper, the low power electrical generator that powered its fire control, and control of its engines. The ship drove full speed into the mud flats around the island, and continued to engage PLA batteries with its aft guns until silenced by 53 hits from 105mm, 75mm and 37mm shells. Amethyst's acting commander then ordered the evacuation of the wounded. The ship registered 19 killed, 27 wounded, and 12 missing during this phase of the operation, in which a total of 60 ratings were evacuated to the Nationalist-held south shore, including the twelve missing, but not the more badly wounded, who ultimately had to be succored by doctors flown in by a Sunderland. (Short Brothers having missed a publicity trick by failing to come up with a new name for whatever variant of the original hull this might have been.)

Consort, ordered from Nanjing to Amethyst's assistance, arrived at 3 and began an action that continued until it was forced to retire from attempts to tow Amethyst off the banks with 10 killed and 4 seriously wounded from numerous hits. Once again, the initial salvo struck control positions and damaged steering, placing it in a perilous position throughout the ensuring action. After breaking off contact, Consort continued downstream to meet the modernised County-class cruiser London and another sloop, the class namesake, Black Swan. At this point it was determined that Consort was too badly damaged to remain in action, and it continued downstream to Shanghai, while London and Black Swan steamed north to try to extricate Amethyst by shooting Communists, a task that proved unexpectedly difficult in spite of London firing 132 8", 449 4" and some 2000 40mm shells, with Black Swan firing an additional 313 shells while peeping around its more heavily armoured compatriot. After taking 13 killed and 15 wounded, and with both forward turrets out of action, London retired, taking Black Swan with it and leaving Amethyst to its own devices. Amethyst was able to escape during the July new moon to join a Far Eastern Station tasked with negotiating a tortuous path between victorious Communists, vengeful Nationalists, Hong Kong taipans, the China Lobby, and the effort to contain the Korean War.

Since there were promotions all around, the Yangzi Incident was obviously a glorious victory, but anticipating objections, the First Lord explained to Parliament that

|

| An illustration I stole from here. |

Perhaps I may at this point anticipate two questions which may possibly be asked: first, how was it that His Majesty's ships suffered such extensive damage and casualties; and second, why they were not able to silence the opposing batteries and fight their way through. In answer to the first, I would only say that warships are not designed to operate in rivers against massed artillery and infantry sheltered by reeds and mudbanks. The Communist forces appear to have been concentrated in considerable strength and are reported as being lavishly equipped with howitzers, medium artillery and field guns. The above facts also provide much of the answer to the second question, only I would add this. The Flag Officer's policy throughout was designed only to rescue H.M.S. "Amethyst" and to avoid unnecessary casualties. There was no question of a punitive expedition and His Majesty's ships fired only to silence the forces firing against them.

All that said, I promised a connection to early computing news, which is this: the Black Swan's impossible arsenal, made practical, the Director of Naval Construction thought, by a Deny-Brown anti-roll active stabilisation device, consisting of retractile, rotating fins with angle of attack continuously controlled by hydraulic vane-type servomotor to create a heeling motion against roll, probably controlled via a variable output hydraulic pump in this installation. Because of the usual problem of response lag, you need a control unit in there --hence the tie in to the history of computing. It is important to stress here that the Black Swan-class, and follow-on "Hunts" were specifically an outside-the-box solution to the apparent threat to British merchant shipping from the resurgent Luftwaffe. There was no way, in October of 1938, to put enough AA at sea to protect British shipping, and British shipowners, from the predations of German air power, and thus make resistance to Nazi aggression possible.

Or was there? A stabilised ship, using the new-fangled technology recently developed to more comfortably deliver cross-Channel passengers, could deliver more AA fire, more accurately and more efficiently (since the crew weren't staggering around on rolling decks). Technology solves an insoluble problem! Or would have, if it hadn't turned out to be a political problem, and had the technology proved, as usual, a bit premature, well established in the cruise ship industry as it now is.

Or was there? A stabilised ship, using the new-fangled technology recently developed to more comfortably deliver cross-Channel passengers, could deliver more AA fire, more accurately and more efficiently (since the crew weren't staggering around on rolling decks). Technology solves an insoluble problem! Or would have, if it hadn't turned out to be a political problem, and had the technology proved, as usual, a bit premature, well established in the cruise ship industry as it now is.

Louis Ridenour (1911--1959), was one of Fortune's "long hairs" at the wartime Radiation Laboratory. In 1946, he returned to his prewar job, lecturing at the University of Pennsylvania, before being recruited away to be Dean of the Graduate College of the University of Illinois in 1947. There, he was known for impressive IT empire building, and in 1959, he was called upon to serve a greater empire, being asked to be Chairman of the National Security Agency, which he did from January until his death due to cerebral hemorrhage in May. Conspiracy theorists ought to be having a wild time with the fact that he died on the same days as his "close associate," Dudley Allen Buck, who will definitely star in his own Technological Appendix when the time is right for the cryotron. I say "ought to," because this was all I found on the web. It doesn't even mention the KW-26! (Again, a Technological Appendix for another day.) Come on, crackpot conspiracy theorists! Do you need Dan Brown to write a book about it, first?

Ridenour gives Fortune a nice survey of the state of the art in computing in the spring of 1949, which, basically means John von Neumann musing, and Ecket and Mauchly marketing UNIVAC and the stillborn BINAC, which is the main focus of Ridenour's attention. Ridenour is fascinated with BINAC's elaborate bit-serial architecture, with two independent CPUs checking each input for mechanical errors. Binary operation was a natural corollary, which is why Ridenour provides his little appendix on binary math, which takes me back to junior high school and somewhat misconceived modules on binary and hexadecimal arithmetic. It was also an operational fiasco, with the Wikipedia account giving a summary of what's clearly a well-worn story in the early history of computing.

The same can't be said about the blither-blather about computers being on the verge of thinking just like people, and replacing "brain work," and eliminating jobs left, right and centre unless the unions get on board and --I guess agree to be euthanised humanely, instead of just being thrown out of work by the robots, real soon now? BINAC's error-checking is key here, since Ridenour can't exactly deny that with the error rate of existing electronic and elecromechanical parts, the idea of a billion-relay computer was beyond ridiculous.

Ridenour may be forgiven for not recognising that the CPU error checking was only one small part of getting BINAC, never mind the billion-relay machine working. I t hink. I mean, it was obviously Utopian, but who knows how long it takes for Utopian technology to become real? Five years, ten years, twenty tops? Never to early to start worrying about other people's jobs for them!

I mean, I guess I shouldn't be too skeptical, because maybe it really did seem like it was just around the corner this time. On the other hand, the story is coming out at the beginning of a recession, which, as usual, the government just can't possibly find the spending room to remedy in the Keynesian way, so that it will necessarily be deep and horrible, and so much for the "Fourth Round" of wage negotations, and, hopefully, farm price supports.

I'm sure that all of this is pure coincidence, so let's look at the computers that are going to replace us real soon now. (Besides BINAC.) First, you have your IBM SSEC, an electromechanical device jiggered up out of the Automatic Sequence Controlled Calculator, various IBM punch tape tabulators that had already been modified to do the tedious chain calculations required to solve second order partial differential equations for astronomy manuals and the Manhattan Project, and a surplus electronic multiplier. At a cost of $1 million, the SSEC was installed along three walls of a former women's shoe store at 590 Madison Avenue, near IBM's headquarters, with Elizabeth Stewart as chief operator. The SSEC needed a chain hoist for its punch tape feed, 12,500 vacuum tubes, and 21,400 mechanical relays. One early user claimed that it would only run about three minutes at a time, and only did about 150 operations in that time.

This all makes the SSEC seem like a shameless bid for publicity. Not surprisingly, its fame has been attached to the Moon effort. SSEC's first use was to produce an ephemeris for the Moon and planets, which is sometimes said to have been used in the Apollo mission. Not to be outdone in the annals of Fifties Big Science, its first paid commission was calculations for the NEPA atomic plane project. SSEC was dismantled in 1951 and replaced in the same room by something called the Defense Calculator, which could hardly be more on the Colossus nose if it tried.

In 1949, Leontief used an early computer at Harvard and data from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics to divide the U.S. economy into 500 sectors. Leontief modeled each sector with a linear equation based on the data and used the computer, the Harvard Mark II, to solve the system, one of the first significant uses of computers for mathematical modeling

The passage seems familiar, and I expect we've encountered it before. Project SCOOP, the Scientific Computation of Optimal Programs, was an attempt to automate simplex solutions to linear programming problems, which is pretty cool, although the applications the Air Force were reaching for were more along the lines of writing optimal work schedules rather than large AIs running the country with rational planning from the Carlsbad Caverns.

Again, the jump from computers that don't work to do simple calculations to computers that do work to do simple calculations that make it possible to write schedules faster to giant artificial brains that replace skilled machinists seems cartoonishly large. The first glimmers of structural-grade titanium takes a back seat to Ridenour's article. We've had titanium bike frames for at least thirty years now, and we're still waiting for AI.

On the other hand, wage demands have moderated. So there's that.

You wrote White Swan, I think you mean Black Swan

ReplyDeleteThat would be, to be precise, the one time that I didn't catch and correct myself after writing "White Swan" for "Black Swan." Also, sometimes, just for variety, "Black Swan" for "White Swan."

ReplyDeleteMy brain is clearly not up to distinguishing the two. The one thing we can agree on is that 1350t is far too little space for 200 people under fire from a battery of 105mm howitzers.