Edit: Oh, heck, I'm leaning in on this one.

Anyway, since the idea that the Brabazon failed because it was predicated on "prewar standards of luxury" came up:

Also,

(If it's random enough, it doesn't need a segue.)

Or. . .

Speaking of

I thought I'd do a bit about these big planes. As you can see, all except the B-36 had double decks. Interesting. Lots of space! You get the picture.

Actually, you may not:

This is the original, rejected single-wheel B-36 undercarriage. There's one of these at the Air Force Museum in Dayton (where the Wright Flyer was somehow flown extensively without ever being photographed in the air between 1903 and 1908), but the standard blurb doesn't give the ground pressure. As completed, the B-36 could take off from all of two airfields in the world. The replacement four-wheel bogies improved this to the point where it could use any B-29 capable field, an accomplishment somewhat undermined by the fact that the Allies had to invent a new classification of AAA-type airfield to accommodate the B-29.

This serves to introduce the point that airfields, and civil engineering are important to aircraft design, and never more so than when we are talking about these gigantic, postwar failures. The Brabazon was originally designed specifically to fly from London to New York, a nodal route that amply justified the largest possible airliner. It also meant flying between just two airfields. That meant only having to improve two airfields to the point where they could take a Brabazon.

This might seem like a narrow range of safety options, but a few nearby fields would suffice to cover the need for a diversionary landing. (And since the aircraft would only have to land, and would not have to take off loaded, they could be much less substantial than the main fields.) It was only if the Brabazon couldn't fly its planned route, and had to divert to Iceland or Gander due to weather, that field qualities became critical. When it became clear at a fairly late stage in its development that this was a possibility, the Brabazon was given a four-wheel bogie that allowed it to land on any field that could take a Stratocruiser---

This might seem like a narrow range of safety options, but a few nearby fields would suffice to cover the need for a diversionary landing. (And since the aircraft would only have to land, and would not have to take off loaded, they could be much less substantial than the main fields.) It was only if the Brabazon couldn't fly its planned route, and had to divert to Iceland or Gander due to weather, that field qualities became critical. When it became clear at a fairly late stage in its development that this was a possibility, the Brabazon was given a four-wheel bogie that allowed it to land on any field that could take a Stratocruiser---

Although this is, again, defining success down.

Since BOAC, amongst other airliners, actually bought the Stratocruiser, it makes a good point of comparison. With a maximum takeoff weight of "only" 148,000lbs, comes closest to anything like practicality. At a direct operating cost of $2.45 per passenger mile, the Stratocruiser achieved paying economy on very long routes. Since it could not make a direct Atlantic crossing, that might seem like a deal breaker, and all I can add is, thank God for Hawaii!

Since BOAC, amongst other airliners, actually bought the Stratocruiser, it makes a good point of comparison. With a maximum takeoff weight of "only" 148,000lbs, comes closest to anything like practicality. At a direct operating cost of $2.45 per passenger mile, the Stratocruiser achieved paying economy on very long routes. Since it could not make a direct Atlantic crossing, that might seem like a deal breaker, and all I can add is, thank God for Hawaii!

So here's another look at the figures of merit from that article on big American bombers, from "Favonius's" destruction of the B-36:

The B-35/41 is standing in here for the Avro Vulcan and Atlantic airliners that will zoom like a Sabre jet!

The Stratocruiser doesn't appear here, although the militarised version, the B-50, does. The B-50 has a higher speed than the Stratocruiser (394mph is the actual Air Force claim), but you will quickly notice that the cruising speed claims are all over the map. Wikipedia has the Stratocruiser cruising at 305mph. The B-50's claimed range of 5800 miles at an operating altitude of 28,000--30,000ft is based on a mission profile that assumes that it will climb to higher and more efficient altitudes and speed up as fuel is consumed, so the cruise speed is an average, at best.

Continuing a comparison of the Stratocruiser with the Brabazon, we can see that the British flagship is down on power. With an auw of 135,000lbs and 14,000hp for the Stratocruiser, compared with 290,000 and 21,200 for the Brab, giving a power loading of 9.6lb/hp for the B-50/Stratocruiser, significantly lower than the 13.7 of the Brabazon. Things are not looking good for the Brabazon, even before we take into account the former's constant problems with the gearing between those mighty Wright Turbo-Compounds and the airscrews. Although the step-down from the coupled Centaurus engines to the airscrews is not so great, there is a great deal more in the way of gearing to go wrong.

Leaving that aside, I promised that I would talk about luxury. What does luxury look like in the air? Like this!

It seems as though BOAC is having some difficulties learning its lesson, because the Stratocruiser is being sold in exactly the same way as the Brabazon, and, for that matter, all those confusing Sunderland-derived flying boat liners.

|

| That's a lot of interior space, for whatever reason. |

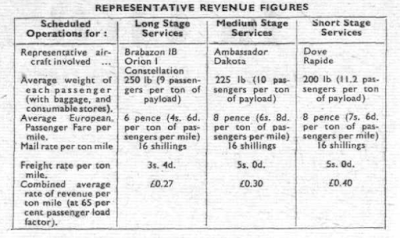

Anyway. Where was I? This whole thing about "luxury." Curiously, this is not what Mr. Masefield says:

What Mr. Masefield says, is that the difference between the Brabazon and the notoriously un-luxurious Dakota is a mere 25lbs of payload per passenger, and the inference is that is mainly taken up with consumable stores on a longer, pressurised flight.

So what's going on? Not to drag this on any further, it's that the reason that the double-bubble two-deck fuselages show up on all of these white elephants is that it is the only way to build a pressurised fuselage big enough to take up the space between the engines and the undercarriage. The space isn't a design ambition. It's an embarrassment. This is even more true of the flying boats, which have a fixed minimum interior space due to the boat hull configuration.

(. . Uhm, Empire, Caribbean, flying boats?

So if you're wondering, dear air passenger, as you rest beside the weary road, where the golden age of air travel has gone, it was never an attitude, because luxury wasn't a design requirement; but rather an emergent property.

If you decide to have a lot of internal volume through depth for some other reason, you are also committing to having a lot of additional frontal area and therefore parasitic drag

ReplyDeleteWhich is particularly true of the "clean" flying boats, starting with the Empires, since you can't raise the engines higher above the water than the top of the hull, and the propeller blades have to be clear of the water. It's also just the start of the problems that taking off and landing on water presents, which is why the "fast" flying boats are such nightmares.

ReplyDeleteI used to assume that Geoff Smith was taking payola from Short Brothers. That is, before I learned about the Seamaster and lost all faith in humanity's capacity for rational thought.