Assyria is perhaps the unique example of a state that revived itself in the early Iron Age, which actually had writing. The case for revival might be a bit weak, were it not for Ashurnasirpal renovating Kalhu (Nimrud) as a capital, building a palace there and decorating it with the "Standard Inscription" that celebrates his rule: State, city, text. More than anyone else can say, the Zhou excepted.

So, why focus on Sargon, instead of Ashurnasirpal? There's a technical and economic reason --the opening to the west; and a military one, in that we get some sense of how large his armies were, and, in particular, his cavalry arm, by virtue of an idealised order of battle for the Field Marshal of the Left's standing force, of 1500 cavalry and 250 chariots. Neo-Assyrian military statistics probably aren't worth the dirt they're written on in general, but this document suggests that a brigade of cavalry and a squadron of chariots are impressive numbers and give some kind of sense of what Assyria's demand for horses might have been like. (Although it is much less impressive than Sarah Melville's minimal estimate of a pack train of 15,000 mules.)

In either case, it is hard to see the demand for horses having a knock-on effect as far as Britain, the other place I'm going to be looking at today. The case for equestrian skills is a bit vaguer, in that a particularly delicious letter from an administrator to Sargon informs him, exasperatedly, that th the governor has been able to round up 500 horses for the army, but only 50 men. "What do I do know?" He asks. Assuming, as seems likely, that the horses are unbroken, it's a good question, for me, as it is for Sargon. What's it telling us?

That Sargon was rich; that he had the resources and political buy-in to build Dur-Sharrukin; that he had to draw on the horse-rearing capabilities of large areas; that his ability to access western Mediterranean trade goods via the overland routes through Anatolia and Phoenicia was important to his success. More on that later!

But there is also the ideological component. What made Assyrian ideas congenial? What made people willing to listen to smiths and horse trainers from afar? It is a fact that Assyria's ancient wisdom, its insights into extipiscy and divining were rooted in ancient oracles. Enigmatic messages out of deepest antiquity are sent by the gods to help us think through the mysteries of their will.

Suppose you examined the liver of a sacrificial animal and found the"Omen of Sargon, who took earth from the courtyard of the . . . gate and built a city [op]posite Agade and called its name ["Babylon,"] and settled [] within it." In Babylon, this is read as an unfavourable omen, reflecting Sargon's hubris. That is not, however, the only way that it can be read. Benjamin Foster describes the "oddest" of the Mari exstiptal models as a simple circle with seven notches around it. Unfortunately for someone who wants to take a leap in the dark and see the liver as some kind of divine model of a city, it is an omen of Naram-Sin related to the inhabitants of Apisal. Naram-Sin is a later Akkadian king not known for building possibly-blasphemous cities. (He did have to survive a zombie apocalypse, though. So that's cool.) He is, however, known for taking the city of Apisal by a breach, which the omen text ingeniously conflates with perforations in the liver, a diagnostic sign for the haruspice.

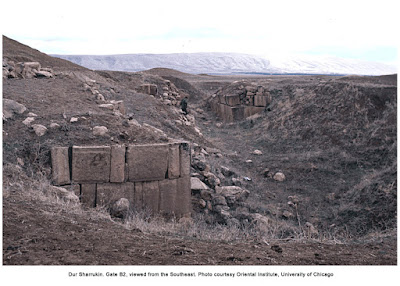

WTF, I'll go all in. Universe: liver: city. The perimeter of the city is the surface of the liver: perforations, breaches, gates. This, it happens, is "Gate B2" of Dur-Sharrukin. I haven't been able to find out, and perhaps we do not know, to which god it was dedicated; but, well, it's a "breach" in the seven-gated city. We don't know, and will probably never know, how Sargon meant us to read it, but that doesn't change the fact that it was meant to be read. The city is the universe.

|

I'm repeating myself, I know. "City establishments" are a powerful idea in regions where the cities actually had to be established, where the state really was being built on virgin soil. The problem here is to ground wispy claims about ideologies and knowledge transfer in empirical evidence. British hillforts first appeared in the Early Iron Age. They may be a well-worn subject, but there's just so much information available about them that they are well worth a look here.