Or, given, seventy years ago today, 6000 ton concrete caissons are being towed across the Channel at a stately 4 knots, a more appropriate soundtrack.

@

Today is the big day. This morning, the first LST will dock in Mulberry A, the artificial port built off Omaha Beach to support the invasion of France. Paradoxically, haste has been urged on its commander again and again, for it is not certain how well, or how long the Mulberries will work. Cherbourg must fall, and it must fall quickly. This is not something that just happens to a fortress of a century's standing, long built under the assumption that it must hold against invaders across the Channel. By controlling the port, the French deny the British the ability to land the battering train that can take the port. The chicken-and-egg problem offers France a measure of protection against a British bolt form the blue as the army does various very important and necessary things in Spain, Italy or Germany. Or Mexico, because if there's one country that needs a Habsburg monarch...

France's civilising mission is conserved by the genius of its engineers. Too bad about those Germans.

|

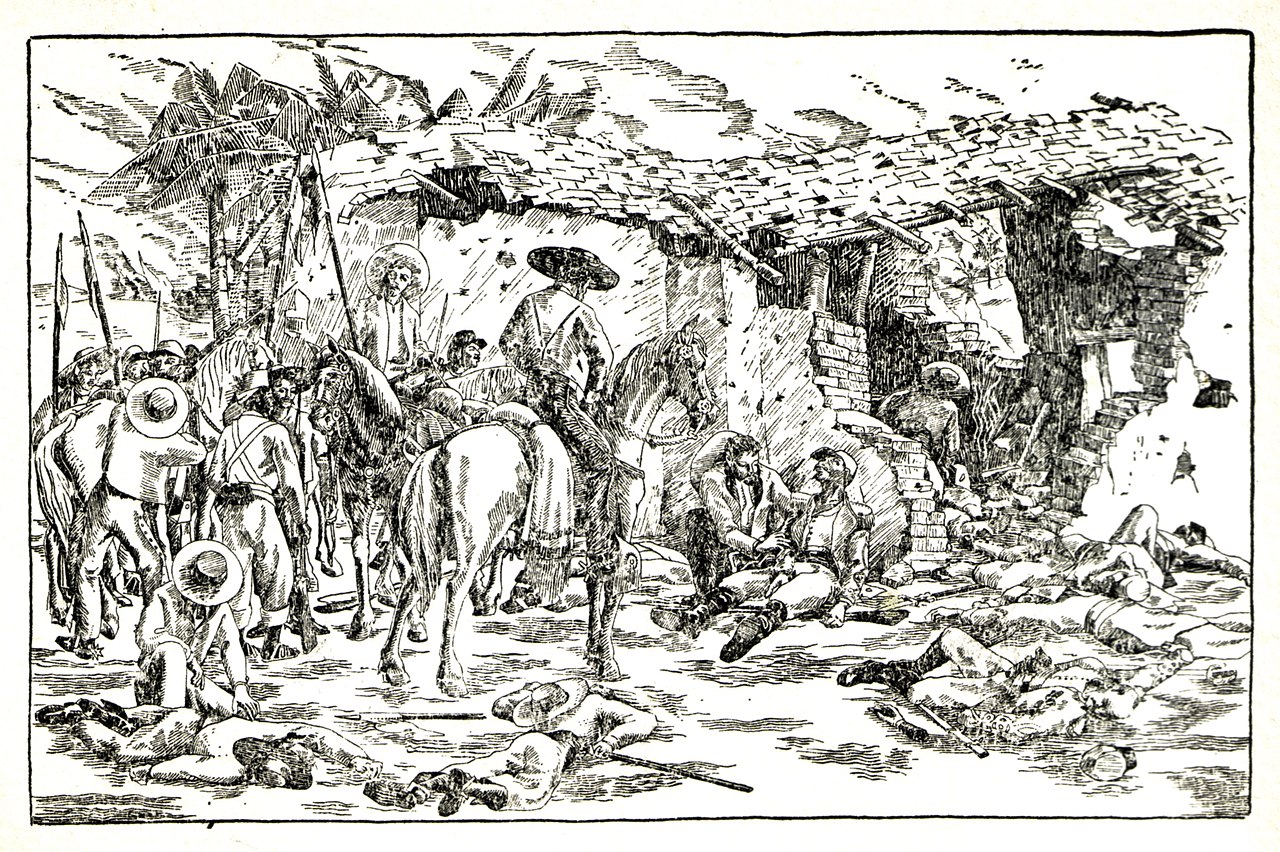

| See? They wear funny hats when they're annihilating our forces. Not a real country. Wiki. |

France's civilising mission is conserved by the genius of its engineers. Too bad about those Germans.

For whatever reason, the Allies have not been deterred, and the situation has developed as long anticipated. An amphibious assault has been made on the beaches to the south of Cherbourg, and an army has advanced inland, cutting off the fortress and presenting its garrison with a contravallation, while defending its own flanks with a circumvallation. The latter is, unfortunately, naturally strong. The inundations of the Douve River, which the Allies have had to cross in the first place, strengthen the line and allow them to resist counterattack with the glamorous, hard-fighting parachute troops of 17th Corps, while three plebeian infantry divisions face north towards the fortress city with the task of reducing the fortress before the Germans can organise a relief. (A fourth division is in reserve.)

Within the besieged fortress are elements of four German divisions: 920th and 921st Regiments of the 243d Division; 1049th and 1050th Regiments of the 77th Division; fragments of the 1049th Regiment as well as elements of the 1057th Regiment (91st Division; elements of all three regiments of the 243d Division, Sturm Battalion AOK 7, all three regiments of the 709th Division, and artillery and antiaircraft batteries.* Some of these units had suffered heavy casualties in the past thirteen days and all were understrength. Sturm Battalion AOK 7, for example, was whittled down to a strength of about one hundred men. This intelligence appreciation omits the fortress units of the Cherbourg garrison, including the coastal artillery, above all the key batteries on Cap de la Hogue, whose importance to the whole port situation will soon become clear.

The composition of the American force is strikingly different from the one facing the Germans in the east, around Caen. There are no armoured divisions, not even any independent armoured brigades/regiments. That does not, however, mean that there is no heavy metal slated for the Cherbourg front. Unlike the British, who have skipped a second round of intensive ordnance development, the United States artillery has invested in a new generation of siege guns. They are not quite the colossal monsters that reduced Sevastapol, but the 240mm M1 Howitzer is a 29 ton monster, pulled in two parts by 38 ton tractors, twelve-and-a-half ton barrel on one trailer, 20 ton carriage on the other. It can loft a 360lb shell with a muzzle velocity of 2300ft/second, something that proved surprisingly hard to correlate with reinforced concrete penetration in a swan around the Internet this afternoon, but this may perhaps be beside the point. The Brialmont works at Liege used 4 meters of unreinforced concrete, and were reduced by Austrian 8.4" howitzers. The higher velocity American 9.2" howitzer was specifically designed to better that performance, and was not going to be left out of the battle, any more than the somewhat lighter 6" and 8" guns, however little discussed the performance of the corps-level heavy artillery. (1, 2, 3, 4)

It was also not going to be unloaded from an LST onto a beach, which brings us back to the port. Unimpressed with the British schedule, the Americans have pressed their port ahead by all possible shortcuts. Captain Augustus Dayton Clark, a constant, unsleeping presence directing the American effort for months, has responded by completing his port three days ahead of schedule. Last night, an unresisting, mute, nervously fidgeting Captain Augustus Dayton Clark, USN (Class of '22) was led off his bridge. In a cynical, upper-addled age, we recognise the symptoms. Captain Clark will die at 90: he is no meth-head; but he has clearly been indulging more than is good for him.**

There is precious little, in the end, that we can say of Captain Clark. The scene of his death, the person who took charge of his funeral, these suggest a comfortable life, as does the ease with which a search for "Augustus Dayton Clark" turns up distinguished Americans of earlier eras. We can understand, given what is soon to follow, why his naval career is soon to end. It is filling in the blanks between 1945 and a death at the age of 90 that is hard. A working career spent in the advertising department of The Philadelphia Bulletin? I suspect that Captain Clark, in his own way, left a vital part of himself on the beaches of Normandy. Romulus buried Remus as a foundation sacrifice to the city of Rome, and when Achilles raised a barrow over the grave of Patroclus on the ringing plains of Troy, he gave twelve Trojan youth to his companion.

Nor twelve youth, or a goddess-borne hero will be enough for the Mulberries,

The image here is pretty staggering. That's why I lifted it from the Beckett Rankine Archives. Beckett Rankine is the firm which originated as Brigadier Sir Bruce White's civil engineering partnership, Sir Bruce White, Wolfe Barry & Partners, and after seventy postwar years of building and improving ports, it has every right to be proud of the wartime accomplishments of its founder, and of Trn.5 more generally. There is, however, far more to it than this. Enough so that a little context and a bit of history is more than enough for a single post. The context, obviously, is the siege of Cherbourg. The history is, well, interesting. As I have suggested, we are lingering over a moment in British history, when peopl who were good at something (civil engineering in general, building ports specifically), picked the country up by the scruff of its neck and set it on a new course. We may suppose that offshore oil was a natural thing for Britain to develop in the postwar era, but there are plenty of petrochemical resources still in the ground (not least among them a great deal of Britain's coal) because it is "not technically feasible" to exploit them. It has to become technically feasible before something like North Sea oil can be brought to market. I do not think that anyone disagrees that this is the way that it became feasible. Conscious intent, or "failing forward?" More likely the latter.

Anyway, enough speculation: time for more history.

On the outskirts of the New Forest, on the estuarine banks of the River Test, across from Southampton in Hampshire, the New Forest tapers to a halt. Erected out of an old wilderness, William the Conqueror's hunting reserve lies on bad soil suitable for pannage the practice of fattening the annual hog herd on fall acorns. That, in turn, requires land in which to hold the hogs, and at the estuarine banks, the problem turns from poor soil to too m uch water. Here lies the old manor of Marchwood Romsey, and, as the Nineteenth Century expanded its mastery over the landscape, manor turned to suburb. By the time World War I came along, it had acquired four churches, a power plant, railway station, and a powder magazine.

World War I presented Britain with novel problems. Dover, its traditional gate to the continent, is a tiny port. That is why the railway connection developed through Devonport instead. Then, the BEF set up shop right across the narrow seas. The solution was the "secret" military port of Richborough: pretty much the same kind of thing, for the same reason, and in the same location as the old Roman base of Reculver.

|

| Source |

For the railway units of the British Army, this was a revelation. To support the army in siege operations, the RE had developed the capacity to build and operate railways on a limited basis. Now the corps came to realise that it would have to be able to conduct rail operations on a much larger scale in order to support a major modern military campaign. Moreover, unlike its continental rivals, it would have to operate rail ports, as well. Veterans of the effort went on to redevelop Dover as a "ro-ro" port in the interwar era, which could take trains across the Channel as trains. (Here is a planning document with more details than you would ever need, although not necessarily a historical focus.)

Jump through World War II, and we get the Marchwood Military Port, the Sea Mounting Centre, today the home of 17 Port and Maritime Regiment, Royal Logistics Corps. That is, the British Army has a specialised unit for conducting port operations, with its own private port. Originally developed during World War I as a support area for the Richborough Port, it came into its own as the site where the Mulberries were developed --although certainly not built.

It is, it seems, on its own face, utterly normal,utterly modern, utterly quotidian.*** The British Army has a regiment -two regiments, in fact-- of port builders and operators. They descend from 931 Port Repair and Construction Regiment of the Royal Engineers (Transportation). This is the unit that has accreted around projects, beginning with the port at Richborough and culminating with an organisation that proposes to repair and even build new ports with the equipment developed for replacing roads and railway bridges with modular equipment.

If you can build a new railway bridge in a hurry with modular equipment, why can you not build a new port with the same? It will, admittedly, have to be quite a big port if it is to be sited off the Normandy coast. If ships drawing 21 feet are to unload at it, the pier heads must be four miles off the beach. A jetty that long is unthinkable, and the Prime Minister is hardly the first to note that one that "rises and falls with the tide" will be required. That insight is to be had in the official history of the Gallipoli campaign, I am assured by some review or another writing in the interwar Army Quarrterly. Not that I can check this claim, now that the copyright trolls have squatted the book (seriously, Australian National Archives? Seriously?) but I think it's in there somewhere.

So that's the project: build a modular port that contains 1400 acres of harbour space --bigger than the Dover port!-- at high water, tow it across to Normandy, install it under fire, and operate it until winter, and perhaps longer. Or, no, build two ports, and give one to the American, considering that it's not going to be possible to find the necessary manpower and tugs without American help. Notice that the whole "railway-Mulberry" thing is pretty organic. There is no way of getting the heavy construction supplies needed to rebuild Cherbourg as a rail port except through the Mulberries. The Mulberries cannot be a substitute for Cherbourg in the long run, because they cannot be rail ports. That does not mean that the Allies do not have plans for an artificial rail port on or near the invasion beaches of France --but that plan is going to have to wait for another post, even if I have highlighted its crucial failing already.

So: transportable, modular port. It's just a bit of civil engineering. How hard can it be? This is probably the place for the only semi-facetious observation that since all major civil engineering projects are today impossible, wrong, too expensive, evil, and surely not worth it in the end, why even try?

@A moment here: Sure, I cite Elgin. Who wouldn't at a moment like this? But there's an actual "Neptune's Triumph" in the all-too-short British classical play list. It lacks the hook that has made Elgin famous, but it's supposed to be quite good, in a Twentieth-Century-Classical-Music sort of way. Take it away, Gerald Hugh Tyrwhitt-Wilson, 14th Baron Berners:

**Details from Stanford.

*** No playlist, regrettably. If that seems obscure, for the sake of those who do not click on links, I will just observe that it goes to 17 Regiment's Territorial component's Youtube Channel. Because it has one, is my point.

Amusingly, the photo on the first page of that Dover blueprint is taken from a vantage point that makes it impossible to see most of the Port of Dover - the Eastern Docks, the enormous road ro-ro terminal, are out of sight in dead ground, while you can only see the (old) Western Docks.

ReplyDeleteIt was in the late 70s or early 80s that the road ro-ro trade and its infrastructure got big enough that Dover was designated as the main port for BAOR, and hence also target for 2 airburst and 1 sea burst SS-20.

Skimming the plan, I had some of the old living-in-Toronto-deja-vu from the endless discussions about how the city was cut off from the waterfront (in this case, by a lakeside expressway rather than a port), and that this was a terrible thing that prevented Torontonians from enjoying the lake.

ReplyDeleteThe solution, apparently, was burying the expressway at the cost of billions of dollars, so that the citizens of muddy York could really enjoy winds blasting across the lake in the winter and the bloating alewives in the spring. Meanwhile, actually existing Torontonians were fine with taking pedestrian ferries to the barrier islands in the summer, and actually existing megastructure proponents were fighting tooth-and-nail to prevent a bridge from replacing one of the ferries, in case the hoi polloi suddenly started driving to the islands.

In the case of Dover, one might suspect that the usual lot of urban renovators might prefer to think around the tax-generating ro-ro port facilities.

Well, it's a very strange, constrained site, especially at the Eastern Docks.

DeleteI'm not sure God wanted a port there. That might be why He put the cliffs in.

ReplyDelete