On 2 March 1954, Tudor I G-AGRI, belonging to a young Freddie Laker's Air Charter, Ltd, was flying 9500ft near Paris on a freight trip from London to Bahrein when it entered cloud. Slight icing was experienced, and the de-icing and anti-icing systems were deployed, due to which the Indicated Air Speed fell from 155 to 135 kt. The captain maintained altitude via electronic control. This capability, built into the Tudor's SEP4 by its now forgotten manufacturer, Smith's Instruments, was developed from the military requirement a bomber's bombsight be able to fly the plane in the targeting run. It was enormously convenient to be able to correct course and altitude via a single knob, or "joystick," as we would say now, but it was also fuel efficient. Taking the plane off autopilot would inevitably lead to course and engine power adjustments, and gas is money. This might, in fact, be why Captain J. M. Carreras did not increase engine power, although the final report notes that "He did not again consult the airspeed indicator." (It is likely that there was no stall warning indicator, as these were facing resistance from the aviation community. At this point, "[n]oticing that the autopilot was applying large aileron corrections and that the directional gyro indicated a turn to port," the captain disengaged the autopilot, with the disruptive results noted, and "the aircraft made a rapid descent in a spiral manoeuvre." The fact that, contrary to regulations, neither pilot was strapped in at the time might explain much of this if we had any clarity about what was going on in the cabin at the time.

Later in the report, we learn that "[t]his resulted in an increase in the angle of attack until flying speed was lost." Saying things without wasting sentences is why we invent new words, and in this case I am lost as to why the word isn't "stall." The upshot is that Carreras regained control and pulled out at 2500ft and the plane continued on its merry way to its refuelling stop in Malta, a flight distance of 2000km, at which point the airframe was "found to be severely overstressed." The airframe dossier says that it was scrapped "circa October 1956."

The relevance of this anecdote is that the Tudor was originally ordered as an interim long range large airliner for the "charters," that is, BOAC and the short-lived British South American Airlines that was for some reason, probably related to possible dollar earnings, created alongside BOAC. The Tudor I, with grossly inadequate seating, was followed by the stretched Tudor II, of which BOAC ordered 79 before returning it to the shop for poor "hot and high" capability, which, for the British aviation historian, will trigger memories of the VC10, or the Ensign, for us antiquarians. The Tudor IIs were on their way to becoming something like the Tudor IVs improvised out of some of the initial Tudor Is for BSAA when BSAA began losing scheduled services for never-explained reasons over the Atlantic: Star Tiger and Star Ariel in January of 1948 and 1949 respectively, with a total of 51 people on board. The plane was withdrawn from service, BSAA closed up shop, and the remaining Tudor Is/IVs sold off for freight or occasionally chartered passenger service.

If at this point you're thinking about tapping the screen where the title says "Comet Inquiry," you're just going to have to wait for the break, because all this talk about air disasters is a great excuse to post

|

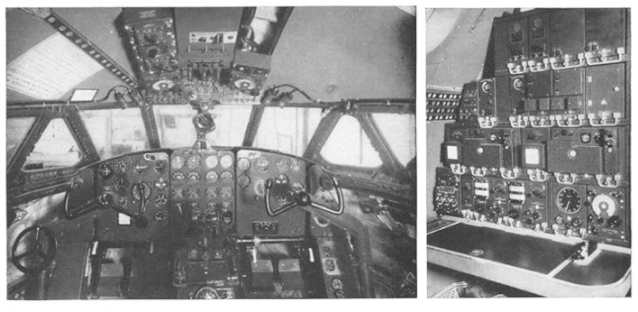

| The Comet's radio shack, instead of that pretty, pretty plane in the air. For a change. |

There's nothing particularly strange about a mid-Fifties airliner crashing. The same week that the Air Charter report came down, inquiries were going on in Malaysia and Ireland over two Super Constellation incidents(1,2). The latter involved a disputed attribution to captain error, an undercarriage retraction mechanism, and a recovery fiasco in which the survivors had to huddle on a mudbank for six hours until the copilot had floundered "painfully" through the marsh to the airport to report the accident. Fun! The "inadvertent landing gear re-extension" is a pretty clear example of the core problem, which is that the modern civil air transport industry was born under war conditions in which technologies were introduced and infrastructure pressed into service without the kind of safety scrutiny that we would expect of a passenger transportation industry, and then it all came home to roost in the Fifties.

No aviation historian has ever advanced an explanation for why two Tudors fell out of the sky in 1948/9 and precipitated BOAC/BA's long term dependence on American airliners. It would seem that we've had a plausible explanation since 1954, but no-one cared. As might be expected at this point it is related to a new technology with limitations that the pilot using it did not fully understand, but we will never be sure because who wants to make a fuss about the early life and career of Freddie Laker, and, after all, no-one died on a Tudor in 1954, as opposed to 1948--50.

|

What was unusual about the Comet is that G-ALYP, flying as BOAC Flight 781, broke up in mid-air without warning on 10 January 1954 just after reaching attitude from takeoff from Rome; and, after the plane was quickly cleared to resume flight operations by the Abell Committee, on 8 April 1954 G-ALYY, flying as South African Airways 201 also crashed, also shortly after gaining cruising altitude after takeoff from Rome. G-ALYP was on its 1200th hour of flight operations when it was lost, G-ALYY its 900th. Oliver Lyttleton, Viscount Chandos, the Tory minister so recently removed (as of November 1954) from his disastrous tenure as Secretary of State for the Colonies, had nothing to do with aviation during his business and political career, but I'm still posting his picture for several reasons. The first is that he's in the paper this month for his premature invention of the Laffer Curve, and I wanted to get that out there. The second is that he's a much better example of the upper class twits in the Churchill cabinet, then the actual minister, a hapless member of an ancient British noble house.

Given the strength of feeling in the British industry at the time, it would have been quite a challenge, politically speaking, not to put the Comet back into service in the spring of 1954, so it is not irrelevant that the minister was born in cossetted privilege, as perhaps a Bevin might have had the steel to keep the Comet grounded. The Calcutta accident inquiry had explicitly rejected the possibility of fatigue failure, so that explanation was very much in the air, and the incipient expiry of structure fatigue life was not going to be remedied by the 50 or so change orders actually issued.

The Cohen inquiry, which could not avoid the topic any longer, was, in fact, set on the track by the upshot of all those change orders. An inspection panel on G-ALYY had been removed to check for signs of stress failure, then replaced incorrectly, perhaps with fatal consequences. This cause for the accident was ruled out, but stress was in the air.

|

| "Trumpian figure," anyone? Who even remembers how popular he continued to be? |

If this sounds suspicious, an "agreed statement" read to the Court of Inquiry during week 5 stipulated that:

1) In ordinary practice, design reliance should not be placed on calculations except as a preliminary step before testing;

2) There were no "mathematical errors or mis-applications of principles in either calculation;"

|

| I was gong to put up a picture of Arnold Hall, but you can see one at the link, and you'll appreciate some prewar aviation nerd humour instead |

4) De Havilland's thinks that Hall's methods were "most valuable as well as a novel contribution to the philosophy on this topic of which important use will be made in the future."

5) It is agreed that there was enough stress in the areas where failure appears to have happened, to cause that failure. But "the pursuit of any question as to the precise value and location of such stresses is considered to be irrelevant to the purpose of the Inquiry."

If this sounds a bit evasive, all I can say is that you probably need to do some course work on old time numerical analysis. There is a point in mid-century engineering design in which "calculations" turned into arguments about the "philosophy" of things. On the other hand that "agreement" sure sounds like everyone agreeing not to sue each other, a good idea when Sir Hartley Shawcross is counsel for de Havilland.

So let us say, just maybe, that the root cause of the Comet fiasco is that the Comet was built too lightly, and that if De Havilland didn't know that, it should have. Exactly how you do you get to that point? For illumination, I am going to turn to the Comet's abortive rival, the Avro Canada C102 Jetliner of 1949, proposed for Eastern-like service between the busy airports of the U.S. east coast, but never ordered.

We can safely discount the idea that Avro abandoned it because the CF-100 was better business; the Jetliner had no business case. We can see this from the fuel consumption/course schematic it published in Aviation Week to make the claim that the Jetliner could be profitable.

In effect, the Jetliner was a missile, designed to go from idling at the terminal to takeoff in 4 minutes, climb to 30,000ft in 23 minutes (this was very roughly the same rate of climb as the RCAF's main interwar fighter, albeit the Siskin had a ceiling of only 27,000ft.), and plunge down from cruising altitude to the terminal in just 17 minutes. Given that the "stacking" crisis was at its peak in 1949, this "step aside, jet coming through" approach was not practical, but that is only the beginning of the problems that arise with trying to turn this fuel-hungry beast into a competitive short-haul airliner.

|

From this we can see the key importance of reducing the structure weight of the Comet to increase fuel load and reduce fuel consumption. Endless arguments with American builders over whether the Comet was operationally viable at all turned on de Havilland's marginal calculations of the number of passengers that could be flown over set distances, and that, in turn, depended on the paying load. One of the reasons that the Comet was deemed so luxurious was the amount of space in its cabin that couldn't be used to carry passengers at the set payloads. This would improve with better engines, and de Havilland as keen to leverage the Ghost-powered Comet into a Goblin/Spectre successor. The airlines' lack of enthusiasm for supplementary rocket power led de Havilland to settle for the Avon as the next generation Comet engine, but the pure turbojet era came to an end with the widespread adoption of early turbofans on the later Boeing 707s and DC-8s, and the VC10. In short, the lightness of the Comet might be a way to build de Havilland's engine division into a business capable of taking on Rolls Royce.

The Comet Inquiry came in the context of multiple inquiries into the failures of major airliners. Very few designs indeed evaded searching investigations into their safety, and some that did, it seems, ought not have been spared, including the Viscount, one of the stars of this blog. I can't help but think that the collegial (repressive?) atmosphere of the Fifties spared airlines such as Northwest, KLM, and others, from the searching scrutiny into their safety cultures that their accident rates warranted. And this is leaving the horrifying Elizabethtown Blitz out of the story. The fifties were a far more dangerous time to fly than the industry admitted, or popular history allows us to remember.

The Comet Inquiry came in the context of multiple inquiries into the failures of major airliners. Very few designs indeed evaded searching investigations into their safety, and some that did, it seems, ought not have been spared, including the Viscount, one of the stars of this blog. I can't help but think that the collegial (repressive?) atmosphere of the Fifties spared airlines such as Northwest, KLM, and others, from the searching scrutiny into their safety cultures that their accident rates warranted. And this is leaving the horrifying Elizabethtown Blitz out of the story. The fifties were a far more dangerous time to fly than the industry admitted, or popular history allows us to remember.

What sets the Comet Inquiry apart is not its fearless scrutiny into the causes of the accident. Had there been such scrutiny, heads would surely have rolled at the Ministry and at de Havilland. In effect, everyone knew what had happened, and that the guilty parties would not be held accountable, because a jetliner was deemed to have been something worth trying, critics be damned. Nor is it the rigour of the crash investigation, which was actually pretty much par for the course. What sets it apart is a public culture of seriousness about science and engineering exhibited by well-attended public hearings in the heart of London. Smart people investigated a problem in public and presented explanations and solutions at the heart of the national Establishment, with a former Attorney General of the United Kingdom as counsel for de Havilland. Progress is at least conceivable in such an atmosphere, it seems. (Spoiler: We'll be on the Moon before you know it.)

link.

.jpg)

First point: I've run the post through my TrooFacts Scanner 3000X and it's telling me Smiths plc is not at all forgotten, it's a £3bn/year FTSE 100 company with 15,000 employees, although these days it mostly does anything with the word "sensor" in it (e.g. airport baggage, medical instruments, nondestructive testing). The avionics division was sold to GE in 2007, but I am sure they're still pretty proud of inventing CATIII Autoland.

ReplyDeleteSecond, a technical appendix to the technical appendix! The point about nostalgic cabin photos telling on themselves is a good one. The very commonly shared ones from early 747s are a case in point; the first 747-100s were, depending on your choices, either underpowered (if you filled up the tanks and accepted a nerve-shreddingly long take-off run) or else shortlegged (if you kept the load calculations sensible and accepted a night stop in fabulous Shemya or glamorous Iqualuit). Out of the launch customers, BOAC chose to put them on the shorter, moneymaker LHR-JFK route which they could do reliably and sent its 707-320s, Tristars, and VC10s on the really long treks, but PanAm wanted them to go to the West Coast, and there are all kinds of stories about them labouring off Heathrow 27R in high summer and gliders over the Chilterns seeing them pass below as they struggled to 5,000 ft by the time they passed Birmingham. Less entertainingly, that meant an unreliable service with lots of short notice cancellations, bumped passengers due to redone weight and balance sums, or visits to gorgeous Bluie 8 or vibrant Goose Bay. One trick was to enlarge First so as to reduce the load while bringing in some money. Hence the nostalgia pix.

The definitive solution was to fix the damn aeroplane already and starting with the -136 they got Pratt & Whitney JT9D-7s, an improvement, or Rolls-Royce RB211s, rather than the JT9D-3A from the outset. Then the -200 aka "Classic" got the choice of D-7s, RB211s, or GE power, and considerably more puff whichever you went with (about 18% more for the R-R). It's possibly worth thinking about the two nicknames for the 747 here: "Jumbo" and "Queen of the Skies", very different connotations.

Third point: there's definitely something interesting in the way the culture of AAIB (or NTSB) has been durable to political change since then. Possibly just because, as JK Galbraith said about Air India, the elite fly and they don't want to burn to death.