|

| A copy of Aphrodite the Warlike, perhaps the cult statue in the temple of Aphrodite Areia on the Acrocorinth. |

Another question, which occurred to me in reverie (five hour bus trips are long trips, especially out of cell coverage on high passes, and I decided not to haul out my gaming tablet): What would the collapse of the Bronze Age order look like in real time to a contemporary? I'm aware of two polished arguments presenting a model that allows us to impose something like a class-struggle revolution. Can they be reconciled with a model in which prestige languages suddenly feel compelled to identify the feminine/belonging to the Goddess, and to borrow from even more prestigious Afro-Asiatic models to do so? That is, a functional model for a parallel adoption of a feminine gender, as opposed to a generative one (feminine endings proliferate because they feel good to say, is my doubt inaccurate summary.)

The two models are those presented in Niall Sharples' Social Relations in Later Prehistory: Wessex in the First Millennium BC, where social revolution is presented as emergent from the archaeological data, and Baruch Halperin's "geocentric revolution," where we get a top-down or superstructural account of what might be seen in an archaeologically-informed way as the rise of the urban sanctuary, a revolution in which a transition from the flat to the round earth provides the cosmological underpinnings to a new model of governance: a model that is going to be complex enough that I'm probably just riding a hobby horse in narrowing it down to urban sanctuaries. (Quick, Classical historians: Define "republic"!)

If I narrow "urban sanctuaries" down to the single best preserved one, I can rope in another prominent work of recent years, Joan Bretton Connelly's unlike publishing sensation, The Parthenon Enigma. Connelly's c tramp around the well-preserved and repeatedly excavated Acropolis of Athens example generates, at least according to her, some real insights. I'm here for her vision of the maidens of Athens dancing in the pannychis of the Panathenaia, on, she supposes, a Bronze Age-era "performance space" consisting of an paved, enclosed plaza on the flank of the Erechtheion , under the Hyades in the night sky, imagined as the daughters of King Kekros, "suspended" in the sky because they have leaped to their deaths from the battlements of the Acropolis' old cyclopean walls (265ff). There's a lot more to the monograph's presentation of the Acropolis as embodying myths of human auto-sacrifice and the ways in which these myths empowered Athenians, especially Athenian women, and underpinned the Athenian republic's insistent demands for social solidarity, but I got there via the image of the maidens dancing and the "Queen of the Night." .The Halperin "model" is pretty exciting for your historian of science. It is fairly obvious from observation of eclipses that the Sun, Moon, and Earth cast circular shadows and that a model based on them being spheres orbiting each other allows for the predicting of eclipses. It is still a pretty staggering insight, implying the existence of "outer space," and inevitably provoking cosmological speculation.. Either Halperin in his diffuse essays or somebody else I read at about the same time takes that a step further. Astronomical thinking reached that point as part of a political project of centalising. The famous story of Thales of Miletus predicting an eclipse. This puts this cosmological/political revelation into the context of Croesus' war with the Medes and the Greek fascination with the "tyrannies of Asi," hence with Cybele the Great Mother and the practice of sacred marriages.

As for what makes this political cosmology so world-shatteringly transformative, Halperin argues that if the Sun orbits the round Earth in "outer space" (itself an awe-inspiring implication of the idea), then it doesn't descend beneath the Earth to feast with the ancestors any more. The solar god is entirely detached from the chthonic earth god. Halperin goes on to talk about a "disenchanted world," but gets grounded quickly enough when he argues that Josiah burning the priests of the "high places" on their own altars was a similar exercise to Ashurbanipal's devastation of Elam (and Josiah's actions at Bethel). They removed the bones from the ancestral tombs, and demonstrated their powerlessness (while removing their value as cult objects) by burning them on the altars, and in fact Josiah's human victims are just dead bones, an argument yo might want to embrace as an apologist for ancient Hebrew religion, or to emphasise that Josiah lacked the power to carry out such an awful purge. (Esarhaddon is another matter, but even he acted only after a generation of rule).

|

| Maiden Castle |

Sharples' archaeological interpretation has the advantage that the only words in which it can be expressed are ours. The thinking of the people who abandoned (for several centuries, anyway) hillforts, elaborate Bronze Age jewelry, and elaborate Bronze Age individual burials is accessible only in the archaeological record, in the objects and the social processes which can be deduced from them with ever greater difficulty as we move from utilitarian (if not explained to the satisfaction of all) burnt mounds to the mystery of the meaning of collective changes in funeral practice. I see that the full text of Social Relations is available on ResearchGate, but as of now I have about ten minutes to finish this post before work, which, while it is not going to happen, motivates me to gesture towards ten-year-old memories to spoil the ending and present Sharples as arguing for a social revolution with an egalitarian ideology with cosmic implications, in that the new death ritual, featuring anonymous mass burial followed by collective "memorialised" internment, emphases group solidarity in death as opposed to the funeral pyres of the Middle/Late Bronze Age and the individual exaltation of leaders and heroes in some kind of "warriors feasting with Odin in Valhalla" spirit.

Social exclusion is indispensable to this kind of society, Sharples argues, channelling Mary Douglas, mainly via the mechanism of witchcraft accusations. Sharples goes on to assume the worst of this social discipline; the fairl common individual burials of Early Iron Age are the remains of all the nonconformist "witches" who were burned at the stake as a lesson for others. In a world with less efficient witch hunting, however, one might well imagine a very substantial fringe of atomised individuals and found groupings similar to more recent "Traveller" communities.

|

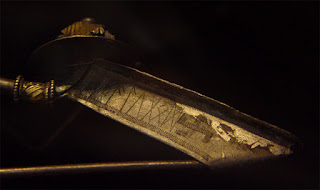

| Vaerlose Fibula, 3rd Century Denmark, with engraved runs |

As to the nature of the cosmology informing these post-revolutionary societies, it would be very difficult to talk about a coherent ideology all the way from the thought-leadership of Nineveh to the backwoods of Dorchester, but we can turn to things. Sharples emphasises that his Iron Age egalitarians abandoned Bronze Age jewelry and makes a tentative foray into body history by talking about the constrictive nature of the Bronze Age jewelry regalia signifying social constraint and hierarchy. This is all very well, but when I went searching for "Iron Age jewelry" I discovered, much to my surprise given that it is common knowledge in the profession, that the omnipresent "fibula," a large safety pin for fastening cloaks at one or both shoulders, was a Late Bronze Age innovation, spreading from the Aegean throughout western Eurasia in precisely the LBA/Collapse/Early Iron Age period.

As a quintessential bit of bling that was probably actually used as a badge of rank in the Roman Imperial army, the fibula makes a poor argument for an egalitarian revolution except insofar as a single (ot two) bits of bling might be cheaper than a regalia consisting of tiaras, gorgets, chest plates, armlets, rings, and the rest of it. On the other hand you can just get a more impressive fibula. The social constriction thing is real, but here let me haul out my Procrustean bed and chop these facts up to fit --doesn't the fibula put more emphasis on the clothes, and, given that a cloak is a cloak, on the fabric and the dye?

At 314ff, Sharples presents the most recent and cogent version of the "Late Bronze Age Collapse as a demonetisation event" thesis of which I am aware. The collapse of bronze as proto-money means the collapse of exchange and of the whole hierarchic society based on elite competition/emulation that practiced it and was made possible by it. The subsequent period was one of widespread experimentation, in which the "extremely bounded" societies which Sharples perceives in Wessex are only one example.

That being said, there is one area in which we see something more general than not: fashion.

If your attention was grabbed by the "tubular loom," here's what we've got.

No comments:

Post a Comment